Back to the Survey Monkey survey I gave my students on November 16. This is a fairly long post, but that's because it's about one of the most important decisions my students had to make.

Question 3: How would you describe the extent to which you prepared for NaNoWriMo?

Many hours, lots of concrete planning 5

A few hours, some concrete planning 6

Hardly any time, hardly any planning 2

No time, no planning 0

Are you happy with the amount of time you spent planning?

Everyone was either glad they’d planned or wished that they had planned more. Except for one person who planned a lot and hadn’t gotten very far at that point. S/he skipped the question.

Writer, Know Thyself: Are You a Plotter or a Pantser?

NaNo says there are two types of novelists: plotters (those who plan) and pantsers (those who write by the seat of their pants). I strongly encouraged my students to be plotters, but that's because when it comes to writing a book as opposed to writing a short story, I'm definitely a plotter. But I didn't demand that they plot just because that's what makes sense to me. Like Richard Hugo said in The Triggering Town, "Every moment, I am, without wanting or trying to, telling you to write like me. But I hope you learn to write like you. In a sense, I hope I don't teach you how to write but how to teach yourself how to write."

This topic—how much to prepare—was a big topic of discussion in our class in the months leading up to NaNo. Many of my students were afraid to do too much planning. They didn’t want to take all the fun and joy out of actually writing their novels. Some believed that “writing with a plan” was cheating somehow.

|

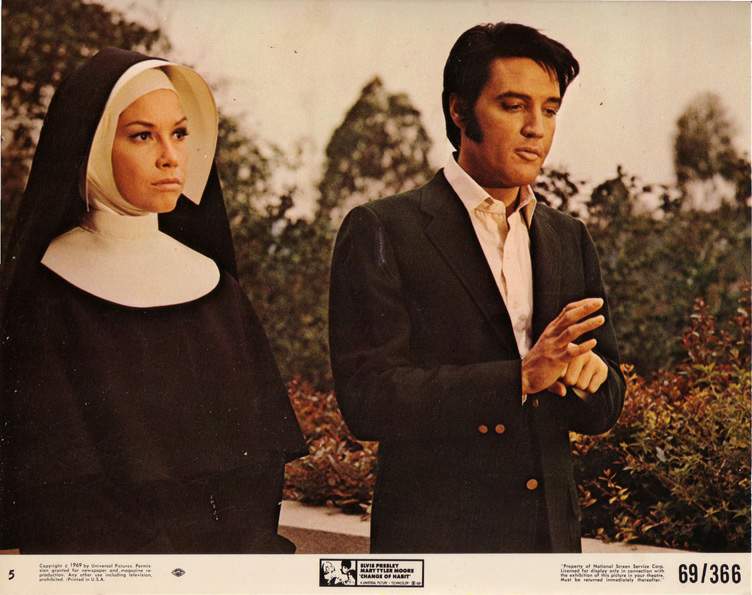

On the Road as NaNo Novel

No matter what you think of On the Road, teaching this novel (or just an excerpt) along with the Cunnell essay are great pedagogical tools to dispel commonly held myths about the writing process.

I would not, however, recommend teaching “The Scroll Version” in addition to or in place of the published version of On the Road. There’s not a big enough difference between the scroll and the published book to generate much discussion. In fact, I think I unwittingly reinforced the idea that a novel written in one month can be and should be published almost as is, which is definitely not what I wanted to do.

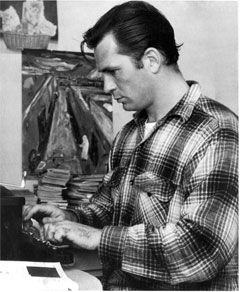

Storyboarding

|

| Photo by Rachel Norman |

I encouraged my students to storyboard their novels, to concretize their plot in broad strokes. We looked at lots of examples.

Even Faulkner storyboarded, as you can see in the photo above.

I pointed them to lots of resources: old-fashioned index cards or post-it notes or storyboard sheets, and new-fangled programs for their computer.

For the Plotters

I provided them a formula. Yes, a formula. When attempting something this large, it helps to have a blueprint, a map, some kind of guide so you know what you’re writing toward. Syd Field’s “Paradigm Worksheet” worked great for this purpose.

I asked my students to consider:

- What’s the basic story? Roughly, what do you think is going to happen? Beginning, middle, end.

- How much time will your novel cover? One week? One month? One year? Five years? Fifty years?

Students came in for conferences. They were required to fill out a paradigm worksheet, inserting their own plot points.

However, if they needed to adapt the worksheet for their own purposes, that was fine. If they needed to write a narrative synopsis instead, that was fine. If they decided NOT to fill this out, they needed to talk about why. Did they firmly believe that pantsing was the way to go, or were they "default pantsing" because they hadn't given themselves time to plot?

This month, I saw many of them begin our in-class writeshops with something sitting next to the keyboard. An outline. An index card. A chart.

For the Pantsers

Some of them, however, didn’t have anything next to the keyboard.

The editors of Wired magazine suggest that, at the very least, you end each day’s writing session with a note to yourself about what to write the next day. “Having the scenes for tomorrow in your head today will give your brain time to work on it even when you aren't thinking about it directly. In fact, you may well find yourself dreaming about your novel, working out ideas in your sleep.”

Writer Timothy Hallinan describes his process as a few months of what he calls “noodling around.”

Long before I begin to write a book, I begin to write about the book. I just open up and let it flow – no censorship, no self-criticism, no pressure. I write about the problem, the setting, the characters. I write biographies of the characters. I let them write about themselves, in the first person. I do a lot of work on what's at stake – what it is, why it matters, how each of the major characters stands on it. (I may even diagram that.) What's the worst that can happen, and to whom? What's the best possible outcome? I make notes for possible scenes and, just for the hell of it, drop my major characters into those scenes and let them begin to talk to each other. (Quite a bit of this material later gets cut and pasted into the book, and then revised as necessary.) I give myself permission to make mistakes.

This is the kind of writing that isn’t always encouraged in creative writing classrooms.

Because how do you grade it? Who does this kind of writing mean anything to--except the writer herself? Is it “real” writing? When you’re writing about your book, does that count the same as actually writing your book? At what point does one become the other?

Hallinan says that usually after pantsing around for 100 or 200 pages, he realizes he’s writing the opening scene of the book, and that’s the moment he knows that’s he "really" writing a book, although he still may not know what’s going to happen.

Hmmmm....NaNoWriMo asks participants to write 50,000 words or about 175 pages.

In a few days, my students will send me the file that contains all the writing they did during November, and I really don’t care whether it was plotted or whether it was pantsed. Whether it's the end result of scrupulous planning or determined noodling. I don’t care if that document is a Supreme Fiction or merely Notes toward a Supreme Fiction. It can be abstract. It can change. And as long as it gives pleasure, the effort, it seems to me, was worthwhile.